The Lean Change method was developed primarily because my team and I needed some way to manage the organizational transformations that we were running with our clients. Over the last five years my focus has changed from running technology delivery projects and programs to running advisory engagements. I had taken the knowledge that our team had gained from executing large-scale agile projects and re-packaged it into a service offering focused on helping clients adopt agile methods.

The good news is that I had early market success, especially in IT. Clearly many organizations wanted to improve the way they were working, and were considering the use of lean and/or agile as an enabler. Being completely transparent, many of these early engagements had mixed results. While I am probably one of the harsher critics of my own work, I was rarely satisfied with the outcomes of these organizational transformations.

My early forays followed a traditional "big C consulting approach". This typically meant performing enough analysis to come up with a target state for the future, and developing a multiyear implementation roadmap. My team and I would typically stick around for the first couple of phases of the change rollout.

It became immediately obvious to myself and my associates that the words "fixed plan," and "organizational change" do not belong in the same sentence. We could immediately see how many of our assumptions behind the target state model, and change tactics used to realize that model, were incorrect the moment we started rolling things out. But it was difficult for us to communicate our learnings to our clients, too many of these folks were focused on tunneling their way through the plan, wanting to get out of the other side. The result was a lot of dissatisfaction from people on the ground, increased organizational dysfunction, and an overall decrease in delivery performance for the organization.

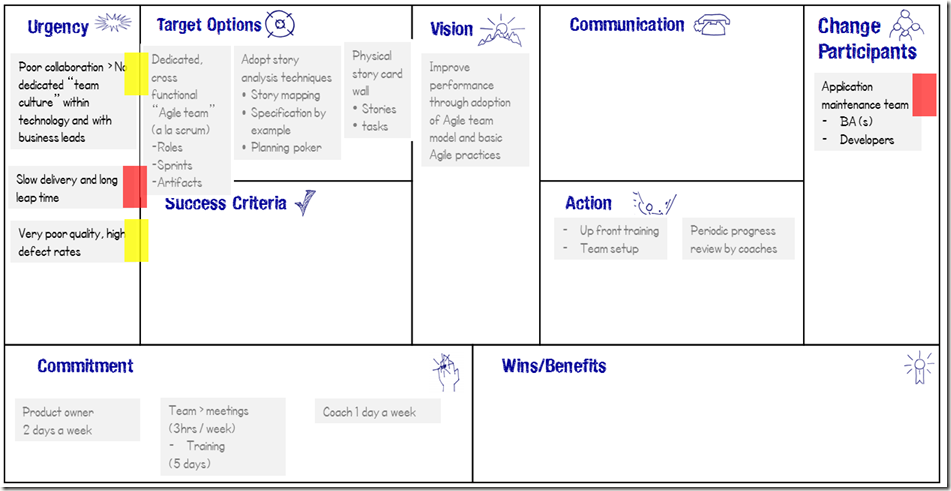

As a side note, many of our agile adoption projects were based on helping clients adopt scrum, this caused interesting challenges in an IT context. We encountered a lot of delivery initiatives that could not easily lend themselves to the idea of cross functional teams, where the majority of team members were dedicated to the work of that team. Often technology delivery was based on the use of packaged software, integration of legacy systems, large data conversion, etc. all which may challenge you to get the value out of a pure scrum approach.

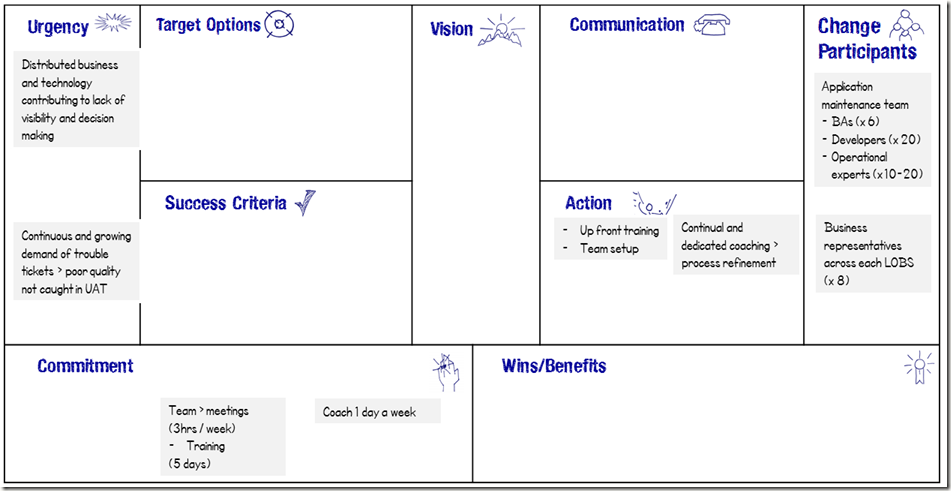

As I began to complement my agile knowledge with lean thinking, and specifically, the Kanban method. Our team looked for clients who wanted help in adopting Kanban as a means of improving the maturity of their organizations. In some cases, adopting the Kanban method resulted in great performance gains for various clients, in other cases people attempting to use the method never quite grokked the continuous improvement mindset. Even more unfortunate were the cases where teams were doing well, but management did not adequately support changes being suggested by people who were adopted the Kanban method, causing the people to eventually become disgruntled, and abandon the change effort. It seemed that even something as lightweight as Kanban required some aspects of managed change to ensure that folks received the guidance and support they need to be successful.

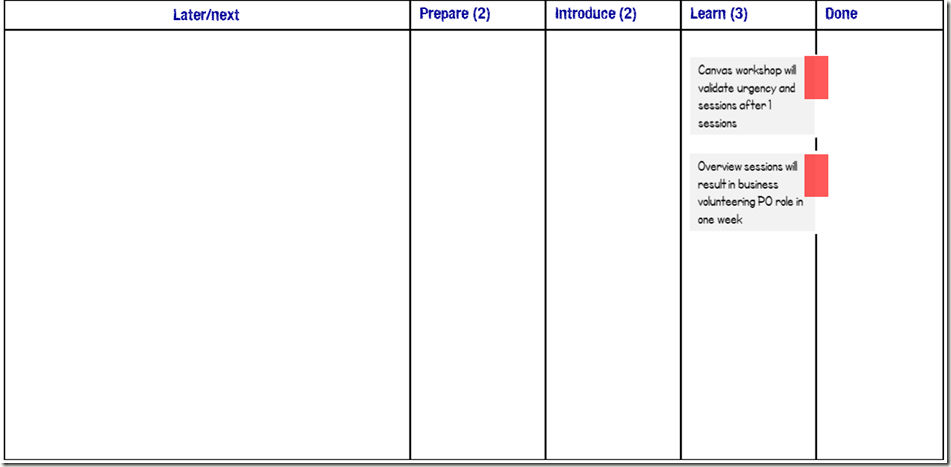

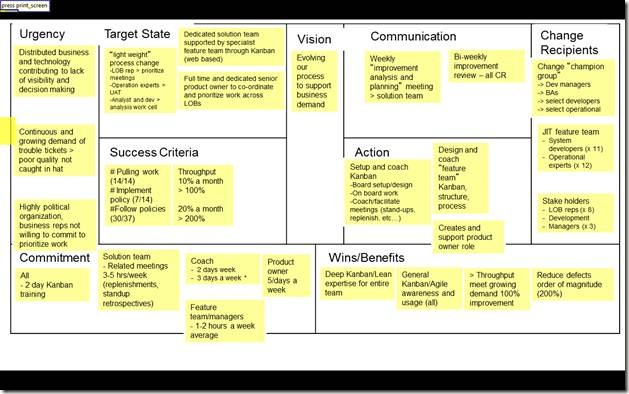

In later change management initiatives our team once again elected to use a more "managed change" approach, but this time, introducing change in small increments, dubbed Minimum Viable Changes. In place of a static plan we used Kanban to manage the change initiative. In lieu of a target state model, we defined a capability model with suggested employee targets over time. We called this new approach "lean startup 4 change". Riffing on the concept that a change initiative can be thought of as a startup, and can use practices made popular by the lean startup method.

In reality, this approach only borrowed a small amount of lean startup thinking, and was really just a form of iterative change using just-in-time planning. There were a lot of challenges with this approach, the biggest one being the disconnect between change agents and change recipients. On the one hand, change agents were able to effectively learn from the results of a previous change iteration, come up with anew set of change tactics, roll the new change out, and incorporate more learning. On the other hand, employees,managers, and other change stakeholders were not able to effectively keep up. This constant modification of change had the effect of creating massive confusion within the organization. Even worse, change was being pushed onto within the organization, leading to change burnout.

Our challenges, highlighted a paradox in managing ambitious change efforts. On the one hand a common strategy and vision is required to align everybody towards a common goal post, and this common goal needs explicit management by executives, managers, and other dedicated change agents. But managed change come with a number of potential drawbacks, drawbacks which tend to severely derail the change effort.

Managed change programs tend to be directed from the outside in, as professional change agents perform organizational analysis, draw up a blueprint for the future, and rollout the change across the organization. Managed change also tends to be directed from the top down, with executives expecting managers and staff to swallow the change that has been dictated to them from on high. Finally, managed change also tends to be rolled out in large batches, causing massive disruption, which is always underestimated by those in charge. The result is change resistance, change fatigue, and a change that often doesn't provide value in the context of real problems as they are experienced by employees on the ground.

What I needed was a change management framework that would allow change agents to model our change as a set of assumptions. The method would then allow me to take those assumptions to mychange stakeholders so that they could validate (or more likely invalidate) those assumptions. My change management framework needed to help me validate proposed changes not only throughdiscussion, but also by testing how people reacted and behaved once the change was deployed, and finally, by testing whether that change was resulting in expected business outcomes, or onlymaking things worse. I needed a change management method that would allow me to make organizational change testable, providing insight to the entire organization around whether a change was succeeding or not!

It was also equally important that any change management framework used insured that the folks being asked to change had a say in what that change would look like. I wanted my change recipients to be co-creators of any change initiative that they were a part of!

Digging deeper into Kotter, and how Lean Startup actually works provided inspiration for this new method.

The Lean Change method is based on the principle that all suggested changes are merely untested assumptions. Using a technique known as validated learning, we introduce change their experimentation, pursuing correct assumptions, and letting go of incorrect ones. The Lean Change method is also based on the principle that change must be cocreated, following a process of negotiation and collaboration. Co-creation must take place between the change agent (the person instigating the change) and the change recipients (the people being asked to take part in a change) throughout the entire lifecycle of the change program. Lean Change is at its best when it's hard to distinguish between change agents and change recipients!

Check out more of the Lean Change method on this site or on my book, The Lean Change Method: Managing Agile Transformation through Kotter, Kanban and Lean Startup Thinking.

![clip_image003[4] clip_image003[4]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEijSQ_FT-oa36vmHtO-WNZ5PRaT3on_nxn63PhPF6xkur4hJLIHI6_NQii1Xophl-VjJ53PzfpMPUuHRFRmmVcn4H3D2J6ufGpKPDZJWyHoA4b6Kxadp45k6hlq78kSBjwUW0dhCvLWUlKA/?imgmax=800)

![clip_image004[4] clip_image004[4]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEjdwKGlbqRu5wI2UYI6clQFK88XqKr7dZbVJqUQXCiyZ6P-bpv9u7yObJA6IM80Tu2Y053CEv90Q5WM5nHgMnf_kbixA1wN3hMDuyHRrNCRIw3LXMuAh4vDg_qhqfi5v0gkJBz2yLjsMcq4/?imgmax=800)

![clip_image005[4] clip_image005[4]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEh-lJXRlyFrwz3d8JFWOLkZnbt36fe4GXLGg7oO4ToUkkkoVFW7URatn8vkjNLIXMmC4gI2xQVPvhwyY8KmJpZ73hyphenhyphenhK9jV6p_W-LvTI7FDY76ahG_66-GiDWpc3adFtoSNJmqUK8sbow7z/?imgmax=800)

![clip_image006[4] clip_image006[4]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgJCwAQzV29_mVaOyWUlCfgrWt8W6NDKAQCTfr-3XwrTbsNmaP1pNtVDXrH1mpZ5K7TNGyrJ7DOUczoITDxJZNwdodNTXRvuwpBL_hw99gWpGswYOE9rq72IyQkonpaDWvDyfezCBEKuTeR/?imgmax=800)

![clip_image007[4] clip_image007[4]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEjQAHfSBkp8JBjbDBzE9WN0cVJkdl_W7znSwCknIRggdTNHwDDbRciX4JKO9S3SqdTeqOO_CC1JgvrmWY3F5Bv64QpNPdOpn0cnXJdxSxgwXjoOX6s73_JLZ5Po66XbQkQ9r576LH0YnEZt/?imgmax=800)

![clip_image008[4] clip_image008[4]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEiSxm5I3ei31K7viqHeG7JaYBQFL-FZYcW3nIusRsxKx4GINfkUSYgwrRGlIZeqqh0oUjWB3_cubizIlJ_zYX4_TAm8VMXW1YuAUFJfNe3X4vnXYEcKEYP_U5X_D9XJW-Dymm_NtxzqnY66/?imgmax=800)

![clip_image009[4] clip_image009[4]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEi2Y7VKgzHYyH0x0fFWbaVoFFkhG0zIy7Dt3xrJqjKQUa4sy8sLgsbZAG-zqaepVlG9j14tXOoh-WiPWrt8nNEkn_AJTvhMvGIJ7Et09BSe73YVS5kzIcjsHqqUzWC4j4mnu87THP9THode/?imgmax=800)

![clip_image010[4] clip_image010[4]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEirzsXPInDYgIlPZtt1PjfWNSTMz919dH7ZPIq6zWzZ21KFBAlnpUoB2X2bvVf378bcqbD94zod7QyrNmGYqKEiM6RrO1ry8GvmSHkQXNzt8JPPkajre0n4AIUs8ZOt5n05hYs_d3tJjIVR/?imgmax=800)

![clip_image011[4] clip_image011[4]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgLYqKm8T-bEz8yrOdxFH7NOrt0S3NUyI819u7fkrTvJaHz9_ymp5VR-fvTZQSMOqbfSsdctViQFoCrag6WDI7LH0drTdKDn5p-s6DkVzsBXEecLOjfeRYTQeNozErPrFcY4CqABwtbpBzU/?imgmax=800)

![clip_image001[4] clip_image001[4]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEg86Wx9c3Q2PsrK3GOmq9pSi6Vs7zD0kYD1ovpXf0LFTTr3JEJZaxyXDTUnZyx_Escwv2zSKZaZ7yZEZNh2CdPMCXTxCkyLV1Y51QXbQ9zHL-XuCVcorLvWYUF9hbPCEDYOGh8Qcqod15FI/?imgmax=800)

![clip_image002[4] clip_image002[4]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEjxPGlcqSArBEvggIIMR-Xwk2R0acyokK9ybEzTr-y69ZRQrQ0V6WJ9cAlCI_EoZkATJMmd902irH2GXSHGJand0UYDn1u6uCkm4cdycdG0_JCvrxa0Rom32O4MWHGO8Y_ol2UrDMkCu11F/?imgmax=800)