A random thought that occurred to me. When they may have have occurred to other technology knowledge workers in Canada.

RIM used to be a real point of pride for Canadians. Not as much anymore. Too many stories of a bureaucratic and dysfunctional organization, a lack of market insight, pulling people off of work mid-project, and just plain not keeping up with the competition.

Sounds like a dramatic overhaul in direction is required to get these guys back on track. I would love to see these three people talk to the executives over at RIM and see if they could stimulate some fresh thinking.

Eric Ries on LeanStartup

You would pretty much have to be living under a rock to not have heard of Eric Ries and the LeanStartup movement. A common misconception out there is that this movement is for kids in garages over at Silicon Valley. It’s really about dealing with uncertainty, and learning how to build sustainable customer value faster than your competitors. Start turning your erroneous assumptions into validated learning. Start leapfrogging ahead of your competitors.

David J. Anderson on Kanban

Moving your organization into leanstartup mode in one go would be a cultural big bang. One that could potentially disrupt your company to the point of bankruptcy. You may want to try a more incremental, evolutionary approach to changing the way you organize the way you work. This is where "capital K" Kanban comes into play. Visualize your work, and limit what you can do to your capacity, start getting agreements between your different knowledge workers down on paper, and get into flow. Bottlenecks to value will become obvious, and you can steer the organization where you need it to go.

Steve Denning on Radical Management

Let’s take a look at how we can get some healthy feedback into our management culture. Radical management is a way of managing organizations so that they generate high productivity, continuous innovation, deep job satisfaction, and customer delight. Radical management is all about helping leaders adapt their organizations to a world of rapid change and intense global competition.

I could imagine a series of webinars, once a week, which featured these folks presenting. What happens next of course is open to speculation.

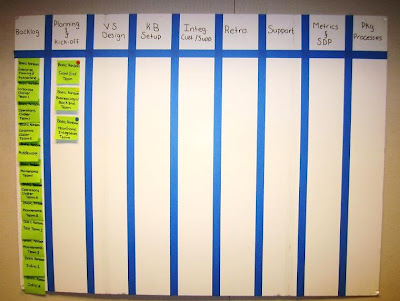

Structured - many teams struggle to discuss problems effectively, the first goal is to find a simple framework to structure the problem discussion. A simple one I use often is setting a simple matrix on a big whiteboard, the top row I place the discussion topics, divide them with vertical lines and then divide the verticals horizontally into 4 buckets, challenges, causes ("why"), easy fix, harder fix. This is a simplified 5 whys approach to root case analysis. I then get the team to brainstorm and start mapping stickies into these buckets. This provides a simple structure to the conversation.

Structured - many teams struggle to discuss problems effectively, the first goal is to find a simple framework to structure the problem discussion. A simple one I use often is setting a simple matrix on a big whiteboard, the top row I place the discussion topics, divide them with vertical lines and then divide the verticals horizontally into 4 buckets, challenges, causes ("why"), easy fix, harder fix. This is a simplified 5 whys approach to root case analysis. I then get the team to brainstorm and start mapping stickies into these buckets. This provides a simple structure to the conversation. Unfortunately all too often this approach results in a

delivery process that looks good on paper, but does not meet the diverse

requirements of different teams, different programs, and different levels of

delivery risk within the organization. The process is often adapted to the

group of knowledge professionals that have the most influence, with the

requirements of other staff and managers having less impact on the framework.

Typical reactions from project staff range from ignoring the process framework

to following it to the minimum level possible to avoid punishment from

compliance watchdogs. In neither case is the desired behavior accomplished, knowledge

workers leveraging the process framework to add value and reduce risk.

Unfortunately all too often this approach results in a

delivery process that looks good on paper, but does not meet the diverse

requirements of different teams, different programs, and different levels of

delivery risk within the organization. The process is often adapted to the

group of knowledge professionals that have the most influence, with the

requirements of other staff and managers having less impact on the framework.

Typical reactions from project staff range from ignoring the process framework

to following it to the minimum level possible to avoid punishment from

compliance watchdogs. In neither case is the desired behavior accomplished, knowledge

workers leveraging the process framework to add value and reduce risk.  We recommend starting the standardization effort with gaining

an understanding of the different work types the organization must process.

Work types can be thought of as a definition profile identifying delivery risk,

size, technical skills required, and effort for particular category of work.

Work types can then be associated with the exact policies required to

facilitate maximum quality and better throughput/leadtime. This approach

facilitates the development of a policy framework that is right sized to the

work, and is flexible enough to change to meet the requirements of different

categories of work.

We recommend starting the standardization effort with gaining

an understanding of the different work types the organization must process.

Work types can be thought of as a definition profile identifying delivery risk,

size, technical skills required, and effort for particular category of work.

Work types can then be associated with the exact policies required to

facilitate maximum quality and better throughput/leadtime. This approach

facilitates the development of a policy framework that is right sized to the

work, and is flexible enough to change to meet the requirements of different

categories of work. Stakeholders and managers tasked with running large-scale

transformations face a great deal of risk. ROI might not be as high as

anticipated, processes may not support certain scenarios, staff may resist

change, and process components may be too lightweight or too heavyweight. A

natural reaction to managing this risk is to try to come up with the perfect

design. There is a desire to try to take into account every possible scenario,

and develop the perfect target state solution. There's often a tendency totry

to design any anticipated risks out of the solution.

Stakeholders and managers tasked with running large-scale

transformations face a great deal of risk. ROI might not be as high as

anticipated, processes may not support certain scenarios, staff may resist

change, and process components may be too lightweight or too heavyweight. A

natural reaction to managing this risk is to try to come up with the perfect

design. There is a desire to try to take into account every possible scenario,

and develop the perfect target state solution. There's often a tendency totry

to design any anticipated risks out of the solution.  Unfortunately, the impact of locking down decisions before

the right kind of information is available is just as risky as making a

decision too late in the process. When a decision is made to early, it is

largely based on assumptions. When the assumption proves to be false, it can be

very challenging for a program to admit the error, and it can take many months

to reverse the design decision. A program that has to much upfront design will

be weighed down by unvalidated assumptions, these unfounded assumptions can

cause the program to go completely off track. While it is important to do some

upfront design, the key is to focus upfront design on decisions that are very

expensive to reverse. Examples include overall organizational structure,

process architecture, tool technology platform, and executive level processes.

Even for these components, it is important to examine the underlying strategy,

and separate fact from assumption.

Unfortunately, the impact of locking down decisions before

the right kind of information is available is just as risky as making a

decision too late in the process. When a decision is made to early, it is

largely based on assumptions. When the assumption proves to be false, it can be

very challenging for a program to admit the error, and it can take many months

to reverse the design decision. A program that has to much upfront design will

be weighed down by unvalidated assumptions, these unfounded assumptions can

cause the program to go completely off track. While it is important to do some

upfront design, the key is to focus upfront design on decisions that are very

expensive to reverse. Examples include overall organizational structure,

process architecture, tool technology platform, and executive level processes.

Even for these components, it is important to examine the underlying strategy,

and separate fact from assumption.  Big Design up Front (BDUF)

is also the antithesis of a Lean approach. Fundamental to Lean thinking is the

notion that large amounts of inventory (unfinished work) causes waste. This

waste materializes in the form of quality problems, unpredictable delivery lead

times, and lowered throughput. When thinking about knowledge work, there is no

physical inventory to remind us of how much unfinished work we have. In this

case our unfinished work are all the requirements, plans, strategies, and

design artifacts that represent a unit of change that has not yet materialized.

Big Design up Front (BDUF)

is also the antithesis of a Lean approach. Fundamental to Lean thinking is the

notion that large amounts of inventory (unfinished work) causes waste. This

waste materializes in the form of quality problems, unpredictable delivery lead

times, and lowered throughput. When thinking about knowledge work, there is no

physical inventory to remind us of how much unfinished work we have. In this

case our unfinished work are all the requirements, plans, strategies, and

design artifacts that represent a unit of change that has not yet materialized.

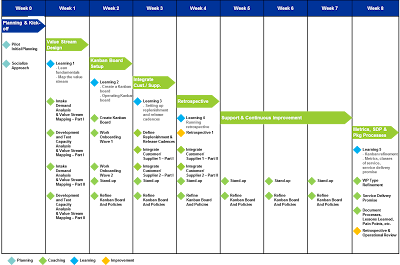

The more we try to create the perfect design the more we

increase our inventory of unfinished work. Larger inventory delay potential

downstream business benefits. More importantly, they reduce the feedback into

the transformation process. Transformations are inherently variable, many

things will not proceed according to plan. When dealing with something as

ambiguous as the way people work, it is inevitable that designs will contain a

large amount of assumptions. Our experience has shown that assumptions are only

correct a small portion of the time. It essential that we test our assumptions

as quickly as we can. This will tell us when we need to pursue a strategy, and

when we need to pivot.

The more we try to create the perfect design the more we

increase our inventory of unfinished work. Larger inventory delay potential

downstream business benefits. More importantly, they reduce the feedback into

the transformation process. Transformations are inherently variable, many

things will not proceed according to plan. When dealing with something as

ambiguous as the way people work, it is inevitable that designs will contain a

large amount of assumptions. Our experience has shown that assumptions are only

correct a small portion of the time. It essential that we test our assumptions

as quickly as we can. This will tell us when we need to pursue a strategy, and

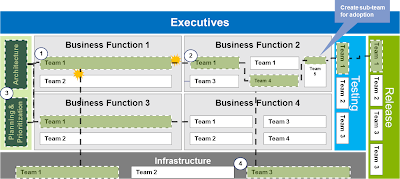

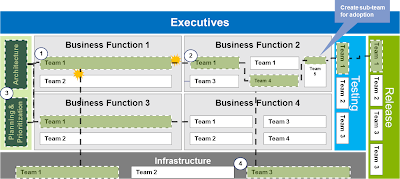

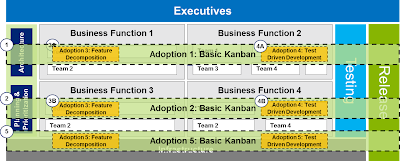

when we need to pivot. We have had great success following an approach that

organizes processes and other design components as a hierarchical set of design

elements. Centralized design decision-making focuses on the top of the

hierarchy, on areas that truly need to be standardized across the organization.

This includes the overall process architecture, overall organizational

structure, role descriptions, and performance metrics. Lower levels of the

hierarchy contain design elements that have a smaller span of scope. An example

of the next level may be decisions and policies that affect individual

departments. The next level down our elements that affect individual programs,

and the bottom are elements that affect individual teams.

We have had great success following an approach that

organizes processes and other design components as a hierarchical set of design

elements. Centralized design decision-making focuses on the top of the

hierarchy, on areas that truly need to be standardized across the organization.

This includes the overall process architecture, overall organizational

structure, role descriptions, and performance metrics. Lower levels of the

hierarchy contain design elements that have a smaller span of scope. An example

of the next level may be decisions and policies that affect individual

departments. The next level down our elements that affect individual programs,

and the bottom are elements that affect individual teams.  Policies and processes that only impact the individual teams

can be designed, and followed by those individual teams. This also means that

those teams are free to adjust those policies when they are nao longer

supporting a high quality approach to delivery. Policies and processes that are

project or departmental wide requirements appropriate manager intervention to

modify, likewise design decisions at the top of the hierarchy require executive

oversight to change. This approach, supported by a measurable and testable

framework, insures that the organization is able to successfully adopt a

continuous improvement approach while still providing a stable framework for

the enterprise..

Policies and processes that only impact the individual teams

can be designed, and followed by those individual teams. This also means that

those teams are free to adjust those policies when they are nao longer

supporting a high quality approach to delivery. Policies and processes that are

project or departmental wide requirements appropriate manager intervention to

modify, likewise design decisions at the top of the hierarchy require executive

oversight to change. This approach, supported by a measurable and testable

framework, insures that the organization is able to successfully adopt a

continuous improvement approach while still providing a stable framework for

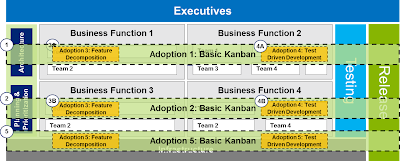

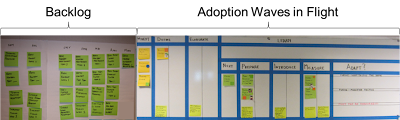

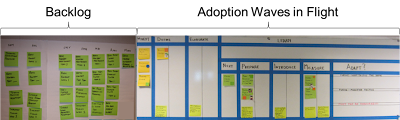

the enterprise.. Starting too many things at once will also lead to too much

work in progress, which as stated previously is a primary source of waste for

knowledge workers. We recommend putting a hard limit around the number of

transformation activities that go on in parallel, and reducing that number if

there is evidence that activities are not being completed in A timely fashion.

Starting too many things at once will also lead to too much

work in progress, which as stated previously is a primary source of waste for

knowledge workers. We recommend putting a hard limit around the number of

transformation activities that go on in parallel, and reducing that number if

there is evidence that activities are not being completed in A timely fashion.